Technology and Memory at Port Burwell, 1929

by PJ Capelotti

Excerpt from "Explorers Air Yacht: The Sikorsky S-38 Flying Boat" (Pictorial Histories, 1995)

Used by permission

There is a destiny about places. For each man there is a piece of territory that calls to him, that appeals to something deep inside him.

-Hammond Innes

Campbell's Kingdom, 1952

When at last we cleared the cliffs of Cape Chidley [Labrador] and felt the fine breeze and swell of the open Atlantic we were as men released from imprisonment in a mine; this stark wasteland was showing a disturbing reluctance to let us go.

-Desmond Holdridge

Northern Lights, 1939

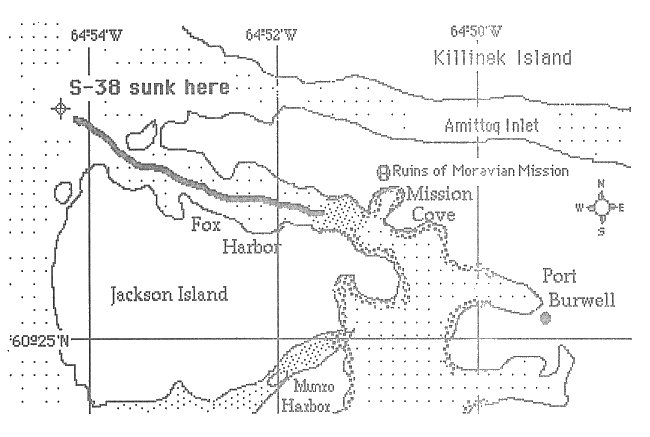

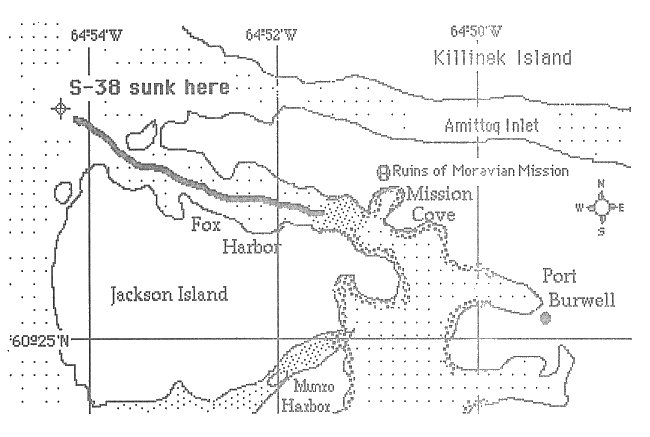

Port Burwell, Labrador, where the Sikorsky S-38 sank on July 14, 1929

Chart by PJ Capelotti.

1

In the 1920s, without a trace of self-effacement, the Chicago Tribune proclaimed itself "The World's Greatest Newspaper." The 1920s in Chicago, the city's "most flamboyant decade,"70 were not self-effacing times. The Tribune was certainly the world's richest newspaper. Circulation nearly doubled between 1920 and 1930, from 436,000 to 835,000. Sunday circulation, by 1930, was over a million. Keeping ahold of a war-time practice, the paper ran an eight-column banner headlines each and every day, regardless of their lead story's news value.

The Tribune's editorial slant, "combative, censorious, sarcastic, Republican, anti-labor, and anti-socialist,"71 derived from its lord and publisher, the Colonel, Robert R McCormick. A sharp-witted iconoclast who introduced many of modern journalism's standbys, including the Sunday rotogravure color section, the Colonel was less successful in his single-handed drive for spelling reform, and even the Tribune eventually stopped using such neologisms as telegraf, frate, and iland.

As much for business as pleasure, McCormick owned several aircraft and loved to fly in them. He hated to wait for anything or anybody, and his private aircraft fleet shuttled him from lodge to office with time to spare. At times he would even take a turn at the wheel, though he generally left the flying to a hired pilot. Two of his aircraft, Buster Boo and Tribby, were named after his bulldogs; two others, Arf Pint and 'Untin' Bowler, were plays on English slang. "He had asked a London hatter for a cork derby to ride to hounds in and had been informed that the item he sought was "a 'untin' bowler, so if you fall off the 'orse you won't 'urt your 'ead.""72

Arf Pint and 'Untin' Bowler were both Sikorsky S-38 amphibians, costing over $50,000 apiece in 1929, and the Colonel preferred them for their ability to alight on lakes in the wilds of Canada, where McCormick owned both vacation hideaways and the pulp mills that produced the paper for his publishing empire. Five of McCormick's aircraft were wrecked, and he was aboard three of them at the time. But he continued to fly. As for the wrecks, he claimed that he had managed to "walk away from one, run away from one, and swim away from one."73

Early in 1929, just before he purchased the 'Untin' Bowler, McCormick was approached by a 33-year-old flier, Parker D Cramer, who sought to renew his own personal attack on the Northern Air Route. Famous already as "Shorty," co-pilot of a flight the previous summer that terminated with an unplanned two-week stay on the Greenland ice-cap and a miraculous rescue, Cramer and his brother William had scratched out a living in the 1920s as barnstormers, flying under bridges, making barely survivable parachute jumps, and selling war-surplus parts for Curtiss JN-4 Jennys.74

Inspired by the commercial possibilities of a transatlantic air route that covered more land than ocean, Cramer had sworn his life to its development and exploitation.

By 1929, the 1919 flight of the R-34 dirigible was still the only successful round-trip flight between Europe and the United States.75 Aircraft, still in their relative infancy, were limited by their short range to making short hops, from New York to Boston, Boston to Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia to Greenland, and so on, across to Europe. New York was the favored terminus for these sea hops, as it had been for Shorty Cramer's midwestern rival, Charles Lindbergh, when Lindbergh flew the Atlantic solo in 1927. But Lindbergh carried no payload, while Cramer sought to use similar technology on a different route to establish a regular, passenger-carrying airline across the North Atlantic.

The Great Circle distance separating Ireland from Newfoundland was nearly 2000 miles, and that was the most direct ocean crossing. But no aircraft existed that could take a payload that far, and in any case the weather over that direct stretch was horrendous at best, with disastrous fogs around Newfoundland and vicious westerly prevailing winds, making a return trip from Europe a continuous war.

Cramer, almost single-handedly, sought to build his bridge north of the bad weather, and he was well aware that McCormick's S-38 was the only sea-going aircraft of its day that could make the 500-mile hops to Europe with any appreciable amount of payload. Cramer's northern route, as he himself wrote, was "several hundred miles shorter between important cities of America and Europe than the proposed Southern Route Via Bermuda and the Azores... The payload of existing aircraft in a jump of 2,000, as is required on the water route, is so greatly reduced as to make the usefulness of the line practically negligible. The Northern Route, with no jump exceeding 500 miles, will permit existing planes to carry normal payloads of profitable size."76

The difficulties encountered establishing a North Atlantic air route were enormous. No infrastructure existed to handle land aircraft or support them once on the ground, and where open water existed for flying boat operations there were no marked channels, no channel sweeping equipment, no loading gear, and no acommodations for pilots or passengers. If Cramer's plan had one obvious flaw, that was it. It took little account of the fact that the aircraft itself was only one aspect of any air operation.

Cramer understood this, but, without a financier behind him, was powerless to change it. The kind of blue-water flying boat that could span the Atlantic would not roll out of Igor Sikorsky's workshop until three years after Shorty Cramer had vanished over the North Sea. He was attempting to establish a regular transatlantic airline using the only technology and geography that existed for him to do so in 1929.

Cramer sought construction engineers who could build an infrastructure where it was needed most, above 55 degrees north, just north of some of the worst climatic and weather conditions in the world. Only as late as April, 1928, had an airplane crossed the Atlantic from east to west, when the Junkers W33 Bremen made the crossing from Ireland to Greely Island, off Labrador. "As early as 1928 Pan American Airways began investigating possible North Atlantic routes. Numerous surveys were made, including one by Lindbergh, who studied a northern route via Greenland and Iceland, making his flight in a Lockheed Sirius seaplane. The very big problem was aircraft range, and Pan American and Imperial Airways did not begin trial flights until 1937 [with the long-range, four-engined Sikorsky S-42.]"77

As Cramer himself wrote: "The proposed route is north of the dangerous fog and storm area of the North Atlantic [and] by crossing Greenland at two different levels it will be possible to come in with a tail wind at high levels and go out at lower levels with a tail wind."78

McCormick, though careful with his money (he once fired a correspondent who turned in a bill of $20,000 for a foreign trip, the only purpose of which was to fulfill a promise the correspondent had made to his mother to one day send her a post card from Timbuktu), almost certainly looked upon the journey as little more than a highly speculatively circulation promotion stunt using his own private long-range aircraft. Such stunts were nothing new. Already in the 1920s newspaper had resorted to printing lottery tickets, giving cash prizes to winners. Competitor papers countered with bigger lotteries and prizes. Despite their dubious legality, these promotions were taken to new heights in Chicago, where sales of the Tribune sky-rocketed. When the government shut the lotteries down, the Tribune turned to new areas of promotion, including extended sports coverage in both the paper and over the Tribune-owned radio station, WGN. Coverage on international events was handled by their own cadre of foreign correspondents, including William S. Shirer and George Seldes.

With the popularity of aviators and their exploits at an all-time high after the transatlantic epic of Lindbergh, it seemed only natural to McCormick to combine his own aeronautical passion with that of the public. In Parker Cramer, he had a famous aviator who had held the world stage for two weeks in August and September of 1928 during his disappearance over Greenland. The Colonel, who was also known as a "notorious optimist on weather conditions,"79 adopted Cramer's plan as his own: to send his Sikorsky S-38 off on the uncharted Great Circle Route to Europe, making it the first aircraft to fly round-trip from the New World to the Old and back again.

By convincing McCormick to sponsor a Chicago entry into the international air derby, Cramer could accomplish what one of the Tribune's lotteries could not: create Chicago as an international city. McCormick and the Tribune could pioneer an airmail and passenger route between Chicago and Berlin. The Colonel could also pioneer a new era in world travel, north over the northern Quebec wastes, over Remi Lake, Rupert House, and Port Burwell. On to Greenland, Iceland, Norway, and Berlin. It could, as the Tribune's pulitzer prize-winning cartoonist John T McCutcheon prophesied, help Canada in opening parts of its vast "waste" territories.80

And, of course, it wouldn't hurt sales.

To accomplish his goal, the owner of the richest newspaper in the world turned in March, 1929, to Igor Sikorsky, owner of a company that had barely survived 1928.

2

In June of 1929, McCormick bought S-38B 114-1, the eleventh S-38 produced at the Sikorsky plant at College Point, Long Island. Registered as NC-9753, powered by two 450 horsepower Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines, McCormick's S-38 received special modifications for the Colonel's planned transatlantic run. The cabin accommodations were removed and replaced by three 100-gallon fuel tanks.

When these changes were in place, on June 28, 1929, the big air yacht was rolled down the gangway at Astoria, Long Island, and into the waters of Flushing Bay. Pilot Robert H Gast was at the controls. Gast, born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1896, had flown for the Canadian contingent of the Royal Flying Corps during the Great War, and in the 1920s worked for the Aeronautical Branch of the Department of Commerce.

In the cabin at the radio was Shorty Cramer: co-pilot, navigator, and radioman. Born in 1896 in Lafayette, Indiana, Cramer had joined the Curtiss Company at the age of 19, and, like Gast, worked for a short time in the Department of Commerce. In August, 1928, Cramer had flown with Bert JR Hassell in the Stinson monoplane City of Rockford, from Rockford, Illinois, to a forced landing in Greenland, where the flight came to a cold and ignominous end. Their resulting two-week trek across the ice cap and re-emergence after being given up for dead, had made them both famous. In April, 1929, Cramer had followed up the Stinson miracle with a flawless survey flight in a Cessna monoplane from Nome, Alaska, over the Siberian wastes, and a return via Nome to New York. Soon afterwards, he had his meeting with the Colonel.

Flipping on the electric starter, Gast gunned the engines and the S-38 "rose from the white capped waters of Flushing Bay as gracefully as a sea gull, despite her load of almost 10,000 pounds...

"It was 2:18 p.m. when the Bowler lifted clear of the water after a 1,000 foot dash through the bay that sent a curtain of spray flying so high it almost hid the boat. She rose like a shot to 1,000 feet, circled back of North Beach and dived low over the crowd that lined the pier. Gast leaned from his seat to wave goodby to the brother pilots who had come up the bay to see him off on his long flight.

"A moment later, as he was climbing over the bay, he waved to Frank T Courtney, the British pilot, who once tried a trans-Atlantic hop, as Courtney sat riding the waves in his seaplane far below the Bowler. Then the great gray Sikorsky flashed on toward the skyscrapers of Manhattan, turned north into the Hudson River valley, and set its course for Albany.

"The Bowler monopolized attention at the tidy airport--which is more like an exclusive yacht club than it is a flying field--from the time the first spectators arrived this morning, attracted by stories in the newspapers of the coming round trip flight to Berlin. A crowd gathered about the ship as the mechanics and radio men began their final inspection. The radio men were sleepy-eyed, for they had worked until early morning hooking up the instrument that is going to keep the Bowler in constant communication with The Chicago Tribune during its days on the unplotted far northern course."81

Cramer and Gast both were both hounded for interviews before the S-38 left Flushing Bay, and both exuded the confidence of the age.

Gast: "The worst part of the whole trip is over--the waiting here in New York. There were a million things to do. From now on it ought to be easy sailing. We've got the right ship, the right maps, supplies every eight hundred miles, and I'll bet you $20 right now that Shorty Cramer and I hop right over there and home again with no trouble."82

Cramer: "Sure, we'll make it right on schedule. We are going to fly as straight to Berlin and back as we are to Cleveland this afternoon. The only thing that can hold us back is the weather and when there is good weather in the Arctic, it usually is good for a week or more. There will be a new mail route from Chicago to Berlin when we get back. I was up as far as Prof. Hobb's camp [in Greenland] last summer when Bert Hassel and I attempted a flight similar to this one. This time, however, we have planned further ahead, and we are making shorter jumps. We'll get there and back OK."83

At 7:09 that night, the S-38 dropped from a smoky sky and landed at the Buffalo Municipal Airport. After fighting a 40 miles per hour headwind up the Hudson and down the Mohawk Valley from Astoria, Gast decided to recuperate overnight at Buffalo rather than chance their original destination of Cleveland. Gast told reporters that people had turned out all along the route to see the S-38. "Several places the roofs of factories and office buildings were dotted with people who had come out to wave to us."84

The improvised stop in Buffalo became typical of the flight, so the Tribune, as did all newspapers sponsoring such expeditions, took great pains to portray the journey as something more than a mere aeronautical promotional stunt. "It will be a scientific survey of the most logical air path between the old and the new worlds,"85 the Tribune with requisite gravity told its readers on Saturday, June 29, 1929, in its usual eight column front page banner. The flight of the 'Untin' Bowler, as Shorty Cramer's scientific survey, took on the genuine significance that the Tribune, in its marvelously detailed explanations, sought so vigorously to portray.

"Its aim is to demonstrate that Chicago is the natural and the best terminus for an airline to Europe and that the northern circle, with land most of the way, offers fewer hazards than any other lane.

"It expects to show the practicability of a terminal in the industrial center of the United States, from which planes could be dispatched to and received from central Europe. Feeder lines already radiate out of Chicago making direct connections with Mexico and Central America, and a five day hookup for mail service between Central America and Europe is possible.

"...the distance from Chicago to the mainland of Europe, because of the spherical nature of the earth's surface, is less than 200 miles farther than the distance from New York to the European mainland.

"...bases already have been established every eight hundred miles along the route and could be set up every 400 miles along 50 percent of the course. The cost of bases every 400 miles would be less than the expense of establishing one of the proposed "floating islands" in the Atlantic. [The Armstrong Seadrome, discussed later.]

"Thus the longest hop on the northern route can be made on six hours fuel, while the other way 30 hours is the minimum. This gives the great circle a payload possibility, feasible in the summer under existing conditions, over which a ship can fly and still keep within the load limits allowed by the department of commerce. The other way gasoline alone far exceeds the load limit.86

On June 30, 1929, the S-38 plowed its way to Chicago amid the worst electrical storm of the season. Gales rocked the ship nearly all the way from Buffalo. En route, in the back of the cabin, Shorty Cramer ran tests on the short-wave radio that would keep the S-38 in contact with Tribune Tower in Chicago. Once the ship disappeared into the Arctic mists, this would be there only link with the rest of the world. The big craft appeared out of the dark sky along the south shore of Lake Michigan in the late afternoon, made a pass over Milwaukee--where the city greeted its fly-by with "sirens, whistles, and cheers,"87 and landed back at Chicago at 7:10 p.m. 500 spectators waited there in the rain for a glimpse of Colonel McCormick's air yacht.

In Chicago, Gast and Cramer were joined by Robert W Wood, the Tribune's aviation editor McCormick assigned as flight correspondent and expedition historian. The three men posed for Tribune photographers while the S-38 received last minute engine checks and McCormick went on his own radio station with an editorial proclaiming the virtues of the flight. Visitors by the hundreds streamed in to stare at the big Sikorsky.

While McCormick promoted science, he also signed an agreement with the aviators, allowing them use of the Sikorsky S-38 for sixty days, whereupon they would return the aircraft to Chicago "in as good condition as they received it, ordinary wear and tear excepted; provided, however, that the AVIATORS shall not be liable for any damage to or loss of said airplane by accident," (a clause Gast and Cramer would ultimately be thankful for) and that the fliers granted exclusive rights to the Tribune to all interviews, stories, news, and that they refrain from publishing anything related to the flight until "after the newspaper publicity concerning the flight or attempted flight has ended."88

As the flyers awaited word from the Chicago weather bureau--whose predictions of favorable weather would decide when the S-38 could take off--only the aircraft's regular fuel tanks were filled, since the ship was less bouyant in the fresh water of Lake Michigan that it would be in the salt water of James Bay, where the auxiliary tanks would be filled. A nasty low pressure system was stalled over Labrador, but a favorable ridge of high pressure was crawling eastward from western Canada to supplant it, and the meteorologists expected the ridge to produce good flying weather for the first two days of the projected five-day hop to Berlin.

"Today we fly to Berlin," Wood Wrote in the Tribune of July 3, 1929. "Our course lies over strange lands where the drone of an airplane motor aloft is unknown...

"Tossed on a pile of furs, skis, and Arctic equipment in the cabin of the 'Untin' Bowler... is a government mail bag. In it is a package of letters addressed in a dozen foreign languages to the Kings and Presidents of as many foreign kingdoms and republics. We hope to deliver that bag to the postmaster at Berlin before another week rolls around--the first air mail to be carried from Chicago to Europe."89

3

On that morning of July 3, 1929, five thousand people crowded along the 8th Street beach to see the S-38 off. At 8:30 a.m., Gast, Cramer, and Wood gave farewell hugs to their mothers and then climbed into the 'Untin' Bowler. Gast waved to the crowd and flashed a bright smile. Shorty Cramer smiled and pointed a finger skyward.Then, amid cheers that resounded from the crowd and the bellows of boat horns along the lakefront, Gast rolled the big flying boat down the ramp and into the lake.

Gast taxied the S-38 out into the lake, planed the hull, then lifted her free of the suction of the water at 8:50, returning at an altitude of barely ten feet to fly past the crowd. "Some in the crowd feared that he would not be able to clear the high bank and the Field Museum, toward which Gast had pointed. But as he neared the obstacle the 'Untin Bowler responded to a slight touch on the controls and climbed safely upward.

"A minute later the big plane floated past the beach again, this time at a comfortable flying height, and the pilot made a graceful salute to the spectators by dipping to the right and left. The flight to Berlin, a pioneer effort toward finding a practical way to cross the Atlantic by air, and to eliminate the hazards that most transoceanic have had to conquer, was on."90

The S-38 winged north at an altitude of 500 feet, stopping briefly at Milwaukee at 9:40 a.m., where the fliers made a quick pilgrimage to the statue of Leif Erikson, and to Sault Ste Marie, where they arrived at 1:40 p.m and spent an hour and a half clearing customs. The first day of flying ended at 7:40 p.m., est, at Remi Lake in Canada, 660 miles from Chicago. The Canadian Provincial Air Service provided refueling there "as the big amphibion rocked in the crystal waves in a background of pine trees."91 Cramer went to the radio and contacted Tribune Tower, while Gast decided that the low rain clouds to the north ruled out their scheduled first night's stop at Rupert House on James Bay.

Before darkness fell, Gast flew the S-38 seven miles to another part of the lake where they loaded an additional cache of fuel. "When they finished, the stars were out and rather than risk the danger of night flying in a strange country, Gast taxied the Bowler all the way back. Foresters stood on the shore swinging lanterns to guide the dark shadow moving slowly back over the lake, its motor shuddering the quiet of the night."92

The weather turned for the worse.

At 6:00 a.m. on July 4, 1929, the S-38 left Remi Lake and the last northern wire connections to Chicago, and headed into the trackless wastes of the sub-Arctic. Visibility was unlimited as they flew over flat, thickly wooded country. A low pressure system sat just over Port Burwell, while another moved east from Minnesota. Cramer's radio reports to Tribune Tower grew more fragmentary throughout the day. At 8:05, the S-38 was over Rupert House, a small settlement of 20 or 30 buildings on the Rupert River on James Bay. The flying boat docked off a sloping beach alongside an old shipwreck. Their they refueled and were off for Great Whale, further north along the shore of Hudson Bay.

During the afternoon, short-wave stations at Elgin, Illinois, and at Port Burwell, showed that the Bowler had taken off from Rupert House and almost immediately ran into rain and poor visibility. "Landing 9:50 Great Whale. Weather bad,"93 read one of Cramer's few messages during the day. "Because of the advantage of distance and lack of interference by other stations, the Port Burwell station had much better reception of the message than at Elgin, where it was said that the listener, who had been on the set since 3 a.m., caught the first whir of the motor at 8:10 and that this continued weakly until the fade-out, which meant that the Bowler was sliding down to a landing.

"On the other hand, the Canadian Marine station on Cape Chidley asserted that the signals were loud. Another station at Hope's Advance, across Ungava Bay from Port Burwell, also had good reception."94

In fact, the fog had forced the S-38 back to Rupert House, where the ship once again tied up alongside the riverboat shipwreck. After taking on more fuel, the S-38 took off again for Great Whale. Caches of fuel--"all of it pretty old"95--were found en route at Eastmain and Port George. At Port George, it took from four in the afternoon until midnight to siphon a few gallons of fuel into the S-38s tanks. Before six the next morning, before the tide went out, the flying boat was in the air again, flying over "green swamp and moss and hills covered with rock outcropping."96 Then, with fog again closing in, Gast decided not to risk a flight to Port Burwell. He picked up the Great Whale River 50 miles inland and followed it to the Hudson's Bay Company trading post at the mouth of the river on Hudson Bay.

Colonel McCormick, when he was able finally to reach the flyers by radio, reiterated his strict orders that the expedition was to use the weather to its advantage and take no unnecessary risks. Gast was ready to attempt the 600 miles hop to Port Burwell, but the weather reported there: 32 degrees and foggy, held him fast.

Throughout July 5 and 6, the weather pinned the S-38 at Great Whale. On July 7, the day they were to have arrived in Berlin, Gast, even with continuing overcast, risked the flight to Port Burwell.

4

The hum from the generators attached to the engines of the S-38 could be heard by radio stations from hundreds of miles away. On July 7, 1929, the radio station as Elgin reported picking up the amphibion's signals for five and a half hours. On July 8, the station at Port Burwell reported hearing the S-38 between 10:30 and 10:40 a.m. only. Other stations were similarly disappointed. The Sikorsky flying boat seemed to be lost amid the vast low plain of Ungava Province, the most desolate of Canadian wilds.

"It is a veritable "no man's land" of muskeg swamps, rock, and stunted forests..." the Tribune lamented. "Of government patrols in this territory there are none--no fire rangers and no forest fire protective planes, for it is all beyond the limit of marketable timber growth, and stunted birch, balsam fir, black and white spruce, and larch, dot the landscape."97

"They'll never make it at this time of year," warned Squadron Leader TA Lawrence of the Royal Canadian Air Force, when interviewed by the Ottawa Journal. "The best thing they can do, while they still have time, is to turn right around and go home.

"They should have waited until the water of the north country was all open and their amphibion of some real use in that territory. Or they should have taken off weeks earlier--about the beginning of June, when winter still held the Hudson Bay district in its grasp and there would have been natural landing fields everywhere on land and sea. "As to the possibility that the flyers might be down and lost in Ungava, Squadron leader Lawrence said: "God help them if they land there... [They] might as well be in the north of Greenland or at the pole itself, for all the assistance and promise nature has to offer them there."98

Four hours after leaving Hudson Bay at Great Whale, the S-38 had sailed into and over Ungava Bay crossed a field of icebergs and headed toward Port Burwell along the jagged eastern coast of the bay. Following the twisted shoreline, Gast had flown the S-38 to within 40 miles of Port Burwell before a looming front forced him to turn the ship around and flee toward the Hudson's Bay Company post at Fort Chimo, on the Koksoak River. A short conference with Cramer and Wood decided that the weather wasn't bad enough to lose the 100 miles back to Fort Chimo, so Gast instead brought the S-38 down to 300 feet, where they sighted an island. They made for a narrow channel near the island where the bigger ice was barred from entering and where the flying boat found an ice-free landing area. The three waited there for the dark, chill skies to clear.

"That was Sunday afternoon," wrote Wood. "There was no sleep that night or the night following.

"Great chunks of melting snow broke from the crevices of the rocks and plunged into the water. At first we thought it was the distant rumble of thunder.

"...three Eskimos hunting seals on the northern shore of the bay sighted the Bowler riding at anchor and scrambled through the ice in their kayaks, defying all laws of equilibrium. The three brown men, with walrus-like mustaches, came and stood thunderstruck before the big kayak with the wings. There ensued a conversation in which Shorty Cramer employed a half-dozen Eskimo words to learn the direction and distance from Port Burwell, on Cape Chidley.

""Kidley ugh," the trio replied, motioning to the northwest. Cramer wrote a message to the Northwest Mounted Police at Port Burwell, stating that we were down, waiting for the fog to clear, 40 miles south of Port Burwell, that the plane and crew were safe, but might be marooned for several days, and if possible to reach us by motor boat."99

With a fine ignorance of the value of money in the Arctic, the stranded crew "gave the Eskimos the note and a twenty-dollar bill."100 They were helpless. Even their radio had to remain silent. In order to use it, the left engine had to be run up to charge the batteries, but the engine could not be cut on for fear that it would pull the ship onto the rocks.

On Monday morning the fog lifted, and Gast took off as soon as it did. A half hour later the fog rolled in again, and again the ship was forced into ice-strewn Ungava Bay.

"All day and into the night the fog hung over the island, covering the mainland a half mile away... At the first sign of daylight, the fog lifted again. We weighed anchor and were in the air again before 2 o'clock. Fog lay in about the hills as the Bowler flew northward. We caught the first sight of the lofty Labrador mountains to the east. Cape Chidley and the whole northern point of Labrador was blanketed in fog with only the tops of the mountains and hills visible. Not a chance in the world of finding Burwell in that mess," Gast shouted back into the cabin.

"We landed in a fjord a moment later. The fog bore down again. This was to be the last of the worst fog on the records of the meteorological station at Port Burwell.

"At 4 o'clock a warm sun climbed into the bay and a northwest wind started the fog southward.

"At 5:50 o'clock the operators of the Canadian Government radio station, who have awaited the Bowler since Thursday, heard the drone of the Sikorsky motors in the clouds. It was not until twenty minutes later that Gast and Cramer sighted the three houses which comprise the settlement, hidden in the tumbling hills of Cape Chidley."101

After this extraordinary battle with the ice and fog of Ungava Bay, the flying boat touched down in ice-strewn Amittoq Inlet near Port Burwell at 7:10 a.m. on July 9, 1929.

5

With the flying boat trapped in Amittoq Inlet, a long, narrow, river-like cut with 30-foot tides, the crew gathered all of the tiny community at Port Burwell to help them save the ship from the murderous ice. Several times on July 10, the S-38 was nearly smashed on the rocks of the inlet. Even if the shifting ice had not held the ship in the inlet, bad weather made the next hop to Greenland impossible. Rain and poor visibility stretched from Port Burwell north along the coast of Baffin Land and across Davis Straight.

"All day long," wrote Wood, "an endless line of Eskimos swung across the mountain, which stands between the harbor, where the fuel is stored, and the fjord, where the Bowler is anchored. Each native bore ten gallons of gasoline on his back. It was a rough, hard climb up a steep cliff, over the jagged mountain and up and down another precipice to the shore, but the little brown men went about their task cheerily. Chesley Ford, factor of the Hudson Bay post here, will give them each a portion of tobacco for their trouble and they will be well satisfied."102

This ad hoc refueling operation was interrupted several times when drifting ice threatened the ship, and when the tidal rush was ready to leave the flying boat high and dry on the rocks. That night the icepack froze in a small natural harbor around the S-38, saving the ship from being swept to sea by the tidal outflow. At midnight, as the inlet waters receded, Gast taxied the plane into the stream and moored it there. The Eskimos had loaded over two tons of fuel into the ship, whose tanks, including the transatlantic auxiliaries, were topped off. The expediton's crew could now only fend off the ice and hope for a break in the weather.

In the morning, on July 11, 1929, an ice jam formed in the inlet, pushing the S-38 onto to rocks and punching a small hole three feet above the waterline. Gast and Cramer repaired the damage, while six Eskimos sat on the wings and tail, pushing away chunks of ice with long poles. After noon, the tide fell back, and left the flying boat stranded on the rocks.

In the early morning hours of July 12, 1929, a chunk of ice as big as a house drifted into Amittoq Inlet and nearly crushed the S-38. Part of one rudder was crumpled, but Gast and Cramer, using the small machine shop at Port Burwell, repaired the damage. At each low tide, the S-38 settled onto bare rocks in the small cove, delivering a beating to the duralumin hull. For the first time, Wood began to doubt they would ever leave Port Burwell on the flying boat.

A large plane is ... unsuited for flying in this country. Save for a few plateaus south of Ungava Bay, we found no landing spaces along the whole route from Sault Ste Marie. On the plateaus a landing could likely be made without casualty, but a crack-up would be almost certain. On the other hand, there is an abundance of water, excepting for a stretch of 150 miles between Remi Lake and Hanna Bay.

"The Bowler was never out of gliding distance of a good-sized body of water, and we have not once used the wheels for a landing... Along Hudson Bay from Fort George to Great Whale, and from there to Ungava Bay fifteen or twenty lakes could be seen from the Bowler at almost any point along the route. Because this region is unexplored the lakes do not show on the map."103

When briefly the ice moved into Ungava Bay on Saturday morning, July 14, 1929, Gast started the engines and taxied the S-38 out of Amittoq Inlet, around a point, and into Fox Harbor, closer to the settlement at Port Burwell. The flying boat was moored there to a seemingly stable plate of ice at the head of the harbor, a few hundred yards from the abandoned Moravian Church. The crew was now ready to leave Labrador for Greenland as soon as the sky cleared.

At 8:00 that night, after the S-38 was moored, the crew returned to the machine shop, located in a small hangar used by Canadian government aircraft in their first aerial explorations of Ungava Bay, where the broken rudder fittings were under repair. Gast and Cramer warmed themselves. Twice that day, with the flying boat resting partly over the ice and partly over open water, they had both slipped and fallen into the ice water, saving themselves at the last moment by grasping one of the many struts of the S-38. The barometer dropped and the wind rose.

"At 9:30 an Eskimo came running over the hills. He had been sent by Corporal McInnes of the Mounted Police, who had been watching the plane, to tell us that the winds had cracked the solid ice. When we arrived at the point where the Bowler had been anchored, the ship was already in midstream and on its way to open water."104

Twenty times the crew of the flying boat and the small band of Eskimos fended off the encroaching ice.

6

Shorty Cramer, though he never showed it, must have been despondent. His second attempt in two years to pioneer a northern air route from America to the Old World had ended in failure, even though he himself had survived again to fly again. His employer's magnificent Sikorsky S-38 seaplane, the most prolific aircraft of its day, had sunk amid ice floes in the middle of July. With his two companions, he was stranded at the scene of its demise--a grey and lonely place called Port Burwell, a now long-abandoned outpost "on the Labrador," in the ancient phrase of the schoonermen, where the bitter elements eventually forced away even the durable Hudson's Bay Company.

In part, Cramer blamed himself. "We "muffed" one thing: While we had cached supplies along the route, this cannot be construed as establishing a base except in the crudest sense of the word. We had made no provisions for handling such large equipment as the Sikorsky and it was due to this omission that we lost the plane... Because of the great range of the tide [at Port Burwell], rocky shores, and without ramps or barges upon which to beach the plane, the best we could do was to fend off the bergs while attempting to fuel."105

Not until the end of July could Gast, Cramer, and Wood board a ship at Port Burwell and begin their journey back to civilization. In the meantime, they lived and cavorted with the natives. On one occasion, Gast replaced the old bell on the abandoned Moravian church and rang it. Hearing the sound of religion for the first time in a decade, the Eskimos responded by gathering at the church in expectation of a sermon.

On July 28, 1929, the message they had given to the Eskimos in kayaks when the S-38 was forced down, forty miles to the south, finally arrived at Port Burwell. "The messengers came across the Port Burwell Harbor, leaping from one cake of ice to another and pushing before them a decrepit sail boat laden with half a dozen seals and three kayaks. They dropped anchor in Mission Cove, pushed their kayaks over board and paddled ashore."106

Notes

70. Joseph Gies, The Colonel of Chicago. (New York: EP Dutton, 1979), p.101.

71. Ibid.

72. Ibid., p. 119

73. Ibid.

74. "[Parker Cramer] drove his [flying] machine under the Kittanning bridge. The present stage of water together with the width of the bridge between the [second and third] piers made the undertaking an unusually precarious one. {Said Cramer:] "Every time I walked across the bridge I got the idea that I could drive my plane under it, and I couldn't get away from the idea. So I concluded to try it and say I am surely tickled I got away with it... At the time the plane passed under the bridge it was travelling 90 miles an hour."" Daring Aviator Flies under Local Bridge, Simpsons' Daily Leader, Kittanning, Pennsylvania, April 22, 1921, William H Cramer Collection (hereinafter referred to as Cramer Collection); "We would certainly like to know just what your minimum rate would be to come up here and stage the [parachute] drops from our plane. Kindly quote prices for one, two and three drops on a single trip up here." letter from GA Parsons, Waterbury [Connecticut] Aviation Co., Inc., to Parker Cramer, Cramer Collection; Cramer's standard stunt flying contract in 1921 called for the "First party [Cramer] to furnish his own airplane and give a thirty minute exhibition of stunt flying (the said thirty minutes to include the necessary climbing for altitude)... and agrees to give [the party of the second part] 25% of any and all passenger flight money received by him ... such flight rates to be fifteen dollars for straight flight of approximately ten minutes duration." Cramer Collection.

75. In the single year of 1975, by way of comparison, 80,000 scheduled flights were made over the North Atlantic, ferrying 8,782,176 passengers and more than half a million tons of cargo. see David Mondey, The International Encyclopedia of Aviation. (New York: Crown Publishers, 1977), p. 260

76. Parker D Cramer, A Northern Air Route to Europe, (1931), p. 6, Cramer Collection.

77. Mondey, Encyclopedia of Aviation. p. 261. Even though Cramer surveyed this route three times--and twice before Lindbergh's survey flight-- the encyclopedias mention Lindbergh's sole flight. As one of Cramer's friends wrote to him in 1931: "It is unfortunate, but true, that anything he [Lindbergh] does seems to be entirely new and publicly accepted, no matter how old or how skeptical the project." Ernest Jones to Parker Cramer, June 12, 1931, Cramer Collection.

78. Cramer, A Northern Air Route, p. 4, Cramer Collection.

79. Gies, The Colonel of Chicago, p, 119.

80. John T McCutcheon, One Angle of the Bowler's Flight, Chicago Tribune, July 5, 1929, p. 1.

81. Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1929, pp. 1-2..

82. Ibid., p. 2.

83. Ibid. The notion that the flight was McCormick's idea is dismissed by a November, 1928, article by Professor William H Hobbs, director of the University of Michigan's Greenland Expedition, who helped rescue Cramer and Hassel from the ice cap in September, 1928, that claims: "The flight is to be repeated next summer, but this time with an amphibian plane..." See "The Third University of Michigan Greenland Expedition," by William H. Hobbs, The Michigan Alumnus, Vol. 35, No. 5, November 3, 1928, p. 4, Cramer Collection.

84. Ibid., p. 1.

85. Chicago Tribune, June 29, 1929, p. 1.

86. Ibid., pp. 1-2. The story went on: "In their flight, Gast and Cramer will face much that is unknown and in addition to mapping an air route they will endeavor to contribute scientific data on the topography of the country over which they fly.

"Bearing northeast from Milwaukee, the Europe-bound Bowler will fly to Sault Ste Marie, where the plane will be cleared from Canadian customs. This formality completed, the ship will continue on to Cochrane, Ontario, and land on Remi Lake, an Ontario forestry control station, 640 miles from Milwaukee. Then the ship will pick up supplies and push on 197 miles to Rupert House on the Rupert River. There at the Hudson Bay Indian trading post, the Bowler and its crew will anchor for the first night.

"The second day the first stop will be 816 miles farther along the great circle, on the north tip of Labrador. There at Port Burwell, on Cape Chidley in Ungava Bay, the flyers will drop down for gas. Port Burwell has a radio station, whose call letters are VCH, but if the 'Untin' Bowler's radio lives up to expectations, its services will not be needed.

"Port Burwell is up north of the fog country on one of the ribs of the world where they have real daylight savings. The sun shines 20 hours a day, so the Bowler and its crew will fly on to Mount Evans, skirt the east coast of Baffinland over Cape Walsingham, visit Holstenborg, capital of north Greenland, and fly up the Stromfjord to Mount Evans, where they will land in protected water and spend the night at Hobbs' camp.

"For more than 500 miles on the second day the flyers will look down on great seas of broken ice and icebergs. There are no towns along this stretch and only a few thousand Eskimos in the country.

"The third flying day will find the Bowler heading across the great ice cap of Greenland, over which no plane has ever flown... The first settlement is 375 miles from Mount Evans and is called Angmagsalik. There is a radio station there with the call O3L, but the Bowler will merely dip down to salute it, continuing on 469 miles to Reykjavik, Iceland's big town.

"Pushing onward the next day, the Bowler will follow the coast of Iceland for 175 miles and then cut across the sea to Thorshaven in the Faroe Islands. By skirting the Iceland coast, the water jump will be held down to less than 300 miles. This jump will offer the greatest hazard of the trip, for it crosses the gulf stream, and where the gulf stream flows flyers catch fogs. Furthermore, the Faroe Islands are only tiny dots in the ocean and do not offer a very large target to shoot at. To offset this danger the Bowler will be flying over a stretch of water comparatively free of large ice, and there will be numerous fishing boats and trawlers--probably the first the flyers will see--plying along the banks.

"If the Bowler makes the Faroe Islands on a bee line there will be no stop at Thorshaven. Glad to be away from the land of the iceberg factories, the flyers will head on toward the Shetland Islands across 210 miles of open water and on to Bergen, Norway, where they probably will pass the fourth night.

"On the fifth morning they will fly 190 miles to Oslo, down Kattegat Strait between the Baltic and the North Sea. From Oslo they will continue 302 miles to Copenhagen, Denmark, and from there to Berlin, 220 miles across land and water, to complete one-half of their journey."

87. Chicago Tribune, July 1, 1929, p.3.

88. Agreement between Robert R. McCormick and Robert H Gast and Parker D Cramer, June 29, 1929, Cramer Collection.

89. Chicago Tribune, July 3, 1929, p. 1.

90. Chicago Tribune, July 4, 1929, p. 3.

91. Ibid., p. 1. Cramer wrote that they flew "through a dozen rain storms" and saw "plenty of lakes most of the course" on the way to Remi Lake. Log of the 'Untin' Bowler, July 3, 1929, Cramer Collection.

92. New York Times, July 4, 1929, p. 2.

93. Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1929, p. 1. Cramer wrote in the log: "Continue on to point about 100 miles south of Great Whale. Fog from ice ... go down to fly over trees but gets thick. Turn around and fly along shore to Rupert House..." Log of the 'Untin' Bowler, July 4, 1929, Cramer Collection.

94. Ibid. To operate the radio in the small aft cabin of the S-38, Cramer reeled out a trailing wire to enhance reception of transmissions from Chicago. "The length of the antenna required for the transmitter is--two pieces of wire each 28 feet from transmitter to far end. If ground is used a little more will be used. Set may be operated very well on the ground or in the water as long as port motor runs. SHOULD THE PORT MOTOR CUT OUT THE GENERATOR MAY BE SHIFTED OVER TO THE STARBOARD MOTOR IN A VERY FEW MINUTES... Reception is ... carried on using the trailing wire which may be let out all the way or just a few feet as desired. Normally reception could be carried on with about ten feet--however more antenna will bring more signal strength and perhaps a little more engine noise... If a landing was made on ground, ice or water the trailing wire could be pulled out and hung on one of the lower wings temporarily with a spare insulator. The antenna reel is easily taken off and wire and fish can be dropped in easily by taking out two screws. See "Instructions for Operation of Radio on Board the 'Untin' Bowler," Cramer Collection.

95. Log of the 'Untin' Bowler, July 4, 1929, Cramer Collection.

96. Ibid., July 5, 1929.

97. Chicago Tribune, July 5, 1929, p. 2.

98. Chicago Tribune, July 7, 1929, p. 1.

99. Chicago Tribune, July 10, pp. 1-2.

100. Ibid., p. 2.

101. Ibid.

102. Chicago Tribune, July 11, 1929, p. 2. Well, not quite. A receipt in Shorty Cramer's notes shows that Chesley Ford, the factor at Port Burwell, collected $200 in wages for a dozen local Eskimos, at the rate of $4.00 a day and $5.00 a night. Tommy, Sr., Henry, and Paulus earned the most, each collecting $16.00 for four days work. See "Wages for Transportation of Gas per Following Natives," July 13, 1929, Cramer Collection.

103. Chicago Tribune, July 13, 1929, p. 2.

104. Chicago Tribune, July 15, 1929, pp. 1-2. Wood continued: "Its nose was in the air and its tail half submerged. A huge chunk of ice had broken from the middle of the stream and was drifting swiftly before the wind with the Bowler lashed to the forward edge.

Had Corporal McInnes and the natives been on the ice at the time it broke away, they would have been blown to sea with the ship. A half dozen persons had been on the ice all day, working on the plane.

"The force of the ice had pushed the hull of the ship upward and the tail downward. One wing settled into the water. Water filled the cabin and the tail sank slowly, although it was not until the Bowler had floated two miles out into the sea that it disappeared. Air compartments in the hull and the hollow wings gave it buoyancy.

"Gast, Parker Cramer and the little colony that has fought with us to save the Bowler from destruction, climbed up the rocks to a high promontory overlooking Hudson Straits, and there watched the plane drift toward a gray horizon and finally slip into the sea. It was a disheartening spectacle. Gast was deeply moved...

"The Bowler went to its grave with both pontoons lashed to the lower wings with rope. A ring strut was snapped in two. The fabric had been ripped from the lower wing. Big rents were torn in the tail surfaces; water filled the hull where it had poured through the hole, and the bracing wires and struts of the plane were pinched. While it would have required several days, the pilots believed it was possible to repair the ship. All the damage was caused by the buffeting of the tide and the battering of the ice.

"At the time the ice broke, we were finishing the repair of fittings for the pontoons in the hope of fastening them on early in the morning. With these repaired, Gast planned to attempt to take off at low tide and fly a mile further inland to Mission, where a small protected body of water offered a possible landing place. A landing there would have been a gamble, but it would have been possible to beach the ship and proceed with repairs. We would have been unable to take off, however, for at least ten days until the ice broke from the end of the cove.

"When we returned from watching the Bowler sinking, Mission Cove was entirely clear of ice..."

Wood writes that the S-38 slipped into the sea, perforce, it sank. A slightly different eyewitness account was provided by Corporal F McInnes, the Royal Canadian Mounted Policeman in charge of the Port Burwell detachment. McInnes wrote that the S-38 "finally drifted out into Ungava bay and was seen to settle down on its tail, leaving only its nose protruding above the water, where is [sic] was held to the ice by the mooring anchor. The aero-boat disappeared in that position in the gathering dusk, and no doubt soon sank to the bottom of the bay." Dominion of Canada, Report of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police for the Year ended September 30, 1929, (Ottawa, 1930), p. 88. McInnes, unlike Wood, does not claim to have actually seen the S-38 sink.

105. Parker D Cramer, Winging Past the Midnight Sun (1931), pp. 14-15, Cramer Collection.

106. Robert Wood, Bowler Fliers Start Home by Ship, New York Times, July 29, 1929, p. 3.

This page is located at

http://www.pinetreeline.org/other8cl.html

Updated September 16, 2002