Welcome to the April- May 2024 edition of The Despatch, the Military Communications and Electronics Museum Newsletter.

Welcome to the New Museum Manager!

The Canadian Forces School of Military Communications and Electronics, CFMWS and the Military Communications and Electronics Museum, and the CFB Kingston community is excited to announce that the new Museum Manager is Rory M. Cory replacing the previous Museum Manager, Karen Young on her retirement.

Rory M. Cory received his Master of Arts in Military History from Simon Fraser University, and his Bachelor of Arts in History and Archaeology with First Class Honours from the University of Calgary. He has over 30 years of various experience in the museum industry including work in programming, curatorial, display design, conservation, and pest control. He has been the Senior Curator and Director of Collections at The Military Museums in Calgary since 2006 and had previously been in various roles at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary since 1994. Rory was lead curator for the traveling exhibits Mission: Afghanistan; For You the War is Over: Second World War Prisoner of War Experiences; and Ring of Fire: Canadians in the Pacific in the Second World War as well as other exhibits at The Military Museums including Victory at Vimy (2007), Defending a Nation: Canada and the Korean War (2013), Wild Rose Overseas: Albertans in the Great War (2014), The Maple Leaf and The Tulip: The Liberation of Holland in the Second World War (2015), and Tour of Duty: Canadians and the Vietnam War (2018). He partnered with Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in Calgary to develop Play Hard, Fight Hard: Sport and the Canadian Military. In 2022 he was awarded the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee Medal for his work as a board member with the Alberta Museums Association and the Organization of Military Museums of Canada. He comes from Mayflower and United Empire Loyalist roots and grew up in London, Ontario.

100 Years Ago - The RCAF Celebrates Their Centennial!

Congratulations to the Royal Canadian Air Force for 100 years of service on April 1, 2024!

The RCAF was first conceived of in 1914 as the Canadian Aviation Corps (CAC) at the beginning of the First World War and was attached to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The CAC had three personnel and one aircraft which was delivered but never used. By May 1915, the unit had ceased to exist.

Between 1914 and 1918, 22,000 Canadians served in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) or Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) with 25 per cent of the RFC officers being Canadians. During this time there were huge strides in air to ground communication that made the use of airplanes viable on the battlefield for reconnaissance and ground support.

Prior to the First World War wireless telegraphy (sending telegraph signals by radio) was used to communicate from the air to the ground. Its main drawback was its size. The battery pack and transmitter weighed up to 45 kilograms and took up an entire seat on a plane, sometimes overflowing into the pilot's area. Due to the size of the equipment, there was no room for a dedicated radio operator. The pilot would have to do everything while flying over the objective: observe the enemy, read the maps, and tap out coordinates in Morse code, all while flying the plane under enemy fire. British pilots could communicate with each other using this method but it was very cumbersome.

The Sterling spark gap wireless transmitter, was the first purpose-built airborne wireless set used by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in the First World War. It was first produced in late 1914 and brought into use in 1915. The transmitter and Morse key were totally enclosed to avoid a spark igniting the petrol vapour in the aircraft cockpit. Communication was in one direction only so the sender, usually the observer in a two-person biplane, had no way of knowing if the message had been received or not. Later spark gap transmitters had both a transmitter and receiver.

The most significant development during the First World War was to the wireless sets themselves. They became more precise, due to the addition of more advanced radio vacuum tubes. These vacuum tubes also allowed for the development of radio telephony (voice communications). Because of the addition of a transmitter and receiver two-way communication became possible. By the end of the First World War, some British fighter aircraft on the frontline were equipped with two-way voice communications via wireless using flying helmets with headphones and throat microphones capable of communication over distances of over 10 miles.

In late 1918, Canada made a second attempt to create a military air force with the creation of the Canadian Air Force that did not thrive due to the end of the war. It was replaced in 1920 with an organization that had a more civilian focus. While it still provided refresher training to veteran pilots, the Canadian Air Force (CAF) members also worked with the Air Board's Civil Operations Branch on operations that included forestry, surveying and anti-smuggling patrols. In 1923, the CAF became responsible for all flying operations in Canada, including civil aviation. In 1924, the Canadian Air Force, was granted the royal title, becoming the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). Most of its work was civil in nature; however, in the late 1920s the RCAF evolved into more of a military organization.

Until 1934 the RCAF depended on the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals (RCCS) for the operation and maintenance of its communication systems. Several RCAF officers had been attached to RCCS for a course of instruction, but the primary responsibility for equipment and manning rested with the army. Due to budget cuts, RCCS informed the RCAF that they would no longer take responsibility for their communications.

In June 1934 four wireless operators transferred to the Royal Canadian Air Force to form the nucleus for the new RCAF Signals Branch. On 1 July 1935, the Royal Canadian Air Force Signals Branch was authorized and began taking over air force communications responsibilities from the RCCS.

During the Second World War, the RCAF Signals Branch was vital to the success of the war effort. Radar technology was in its infancy, very secret and very important to rapid communications. The importance of telecommunications came to the fore. This is evidenced by the size of the Telecommunications Branch in 1949. The RCAF Telecommunications Branch establishment was set at 165 officers and 1700 other ranks out of total RCAF establishment of 14,500. By 1962 the Telecom branch had expanded to 6000 personnel.

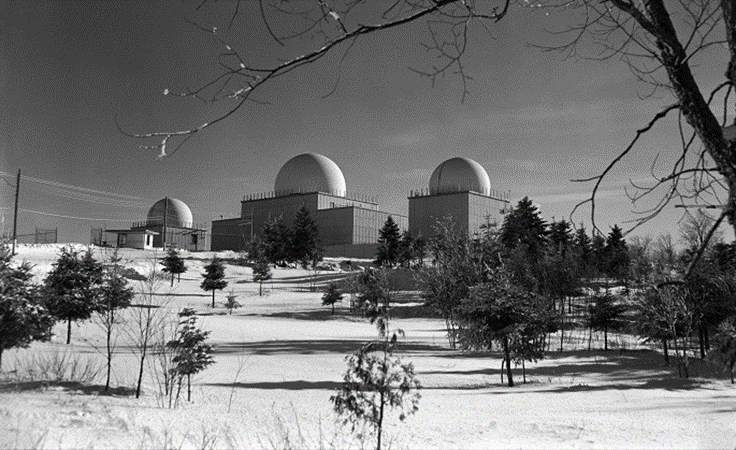

In 1951, the Pinetree Radar Line construction commenced as a joint Canada - USA project. Radar early warning stations were placed to counter the Soviet air threat against North America. Initial radar stations were fully manual air defence systems with both aircraft control and early warning functions. The stations were organized into geographical sectors. (As part of this expansion women were again enrolled in the RCAF [the wartime Women's Division was disbanded in 1946] and by 1954 airwomen were eligible for overseas postings.) The Pine Tree Line was replaced by the Distant Early Warning Line (the DEW Line) by 1957. In 1988, the North Warning System (NWS) began operations, replacing the DEW Line and the remaining Pinetree Line stations. This is part of the joint US-Canada North American Air Defence (NORAD) System that continues operations to this day.

To all of the Communication and Electronics Branch Air Force Members, past and present, congratulations on your centennial!

Foymount, a Pinetree Line station in Ontario

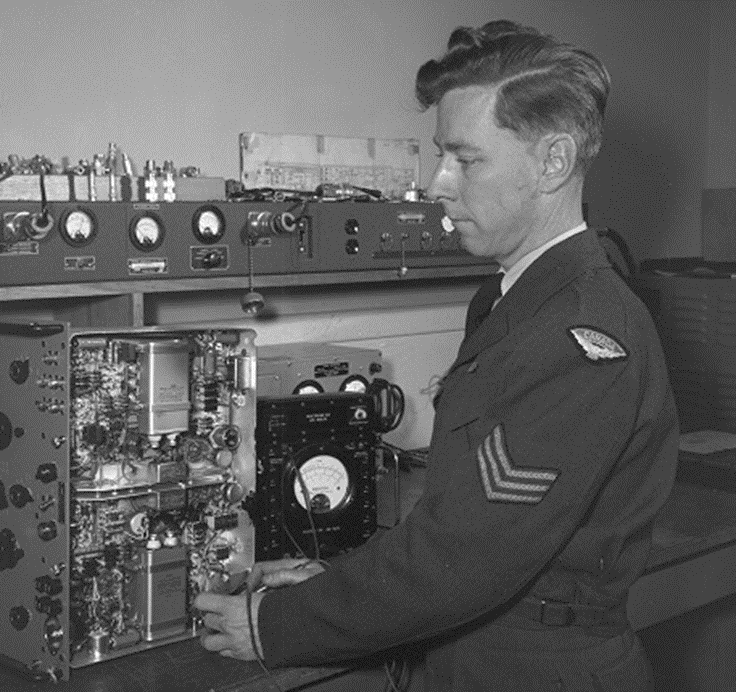

Sgt Gerald Watson checks radar test equipment at Foymount.

Karen Young, Military Communications and Electronics Museum Volunteer

80 Years Ago! The Invasion of the Italian Mainland

"The immediate objective of the spring offensive was the capture of Rome, still blocked by the control of Monte Cassino by the Germans which commanded the approach to Rome from the Liri Valley on the southeast. As a prelude to the attack up the valley a wireless deception scheme was mounted in late April. To convince the enemy that the 1st Canadian Corps was to participate in an assault landing to the north on the Tyrrhenian coast, wireless sets from every unit in the Corps except infantry were assembled at San Severino near Salerno. Links were operated to phantom headquarters of the US 36th Division, 1st and 5th Canadian Divisions and Headquarters Allied Armies in Italy. The operators enjoyed the work, particularly while they conducted a real rehearsal for an imaginary assault. Ample evidence discovered after the war attest to the success of the ruse in drawing German reserves away from the area of the intended frontal attack." Pg 139, History of the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals, 1903-1961

The Winter Line was fortified with gun pits, concrete bunkers, turreted machine-gun emplacements, barbed wire and minefields. It was the strongest of the German defensive lines south of Rome. About 15 German divisions were employed in the defence. It took the Allies from mid-November 1943 to June 1944 to fight through all the various elements of the Winter Line, including the Gustav and Hitler Lines. The spring offensive of 1944 opened on the 11th of May with the breaching of the Gustav line. The attack focused on the capture of Monte Cassino with the 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade and the 8th Indian Division pushing forward. The Canadian squadron command tanks had as many as four wireless sets inside. One No.19 set communicated with the squadrons tanks, a second No. 19 set to the regimental headquarters, a No. 38 set to the Infantry platoon accompanying the squadron and the No. 18 set was the lateral link to the other squadrons. What allowed the Canadians to move forward so quickly was the high standard of training in tank-infantry communications. This was supported from the rear by an extensive wireless command network at Brigade headquarters and exceptional field work in laying line in the dead of night.

The Hitler Line was the next target as part of Operation "Chesterfield." The line was breached on 23 May 1944 on the British Eighth Army's front by the 1st Canadian Infantry Division and 5th Canadian Armoured Division, which attacked with II Polish Corps on their right. The first to breach the line, at Pontecorvo were the 1st Canadian Division's 4th Princess Louise Dragoon Guards. The Polish Corps captured Piedimonte on 25 May, and the line collapsed. To prepare the Signal plan for the operation was staggering in its complexity. At no time during the day of attack was any telephone line out longer than 30 minutes and there was an alternative route always available. As wireless sets were inevitably destroyed Signals officers and men would carry up to the front replacement sets. Gallant work was done by Signals operators, despatch riders and lineman and many were wounded.

The advanced through the Liri Valley continued and the 5th Canadian Armoured Division worked on crossing the Melfa River on the 24th and 25th of May 1944. Signalers were used for creating Traffic Control Points, linked by wireless so that the Provost Marshall kept the armour informed of routes available for a breakthrough. This method was so successful it was used repeatedly in future engagements.

By the 27th of May, 1944, the 11th infantry Brigade of the 5th division were in Ceprano. Lineman were sent into the town to set up the exchange and lay the lines to the battalions through heavily mined areas. All needed to be in readiness for the Headquarters of 1st Corps arrival on May 29th. Independently, the lines officer of the three signals units reorganize their systems of laying cable as a result of this operation. Crews built line along a central artery, off which detachments built laterally to subordinate formations. In future all formations have to be prepared to lay line from every new location to the central axis.

At the Hitler Line 1st Canadian Corps had fought its first full scale battle with the aid of a complex but highly efficient signal system.

Museum / Mercury Shop Reopening!

With the end of the PSAC-UNDE strike on April 19, 2024 the MCEM and Mercury Shop will reopen soon. Please check the MCEM website for further announcements! https://www.candemuseum.org

May 17, 2024 World Telecommunications and Information Society Day- Free Admission to the Museum

The origins of World Telecommunication and Information Society Day date back to the signing of the First International Telegraph Convention on 17 May 1865, which marked the establishment of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

In November 2005, the World Summit on the Information Society was called upon the UN General Assembly to declare 17 May as World Information Society Day to focus on the importance of Information and communication technologies (ICT)

In 2024, the focus is on Digital Innovation for Sustainable Development.

In honour of this day acknowledging the importance of telecommunications, museum admission will be free.

Volunteer Appreciation!

On April 16, 2024, Rory Cory, the new Museum Manager held a meet and greet at the museum for our current volunteers.

Our volunteers from both MCEM and RCEME were in attendance as well as representatives from the Branch and from CFSCE. Rory Cory welcomed our volunteers and noted that volunteers are a core part of any museum's operations, and that that he looks forward to growing the volunteer cadre (both in person and virtually) and having our volunteers back on board following the strike. The Commandant and the SCWO were in attendance as well and had some strong words of appreciation for the deep value that volunteers bring to the table. The Commandant even indicated that she might volunteer herself after she retires! There were also discussions with CFSCE personnel about expanding the pool of volunteers from their ranks. Volunteer mugs were handed out in appreciation. The museum looks forward to making this an annual event, with greater attendance following the end of the strike.

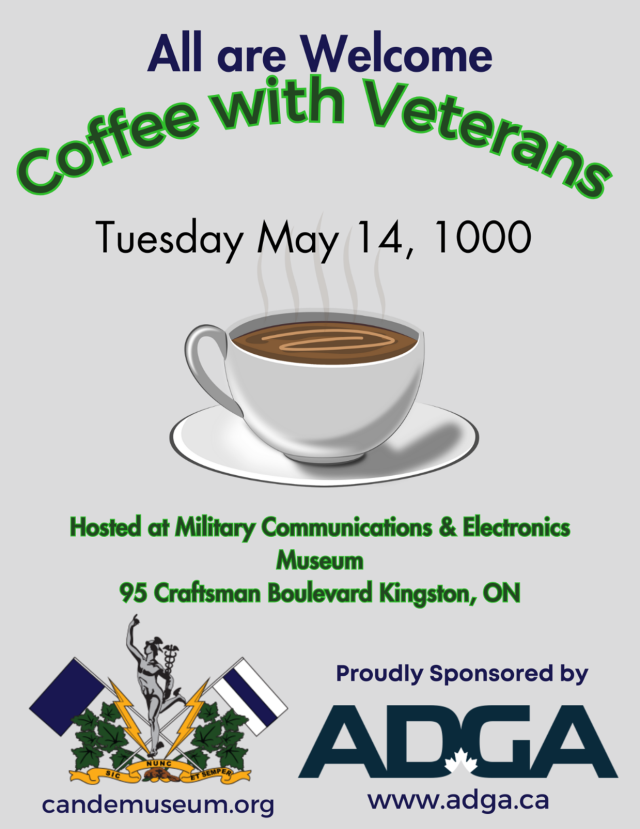

Coffee with Veterans

Join us for Coffee with Veterans on May 14, 2024 at 1000. Proudly sponsored by ADGA!

Not Forgotten – Lieutenant Ernest William Auld (402203)

References: A. https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item/?op=pdf&app=CEF&id=B0305-S049

B. https://cmea-agmc.ca/sites/default/files/abbreviations_used_in_service_records.pdf

D. https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/205286/ernest-william-auld/

E. https://www.google.com/maps/place/Longueau+British+Cemetery,+80330+Longueau,+France/

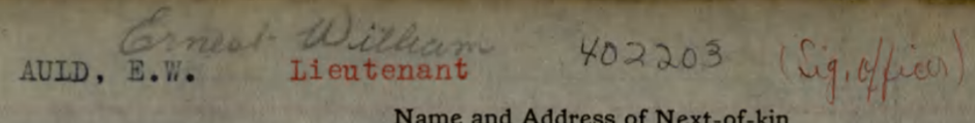

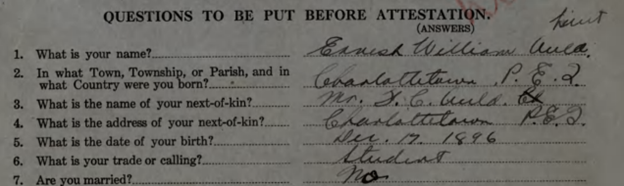

Ernest William Auld was born in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island on 17 December 1896. He enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force on 10 September 1915 (at the age of 18) as a Signal Officer.

Ernest completed his Signal Officer training on 11 Feb 1916, and was transferred to the Brigade Signalling Base, posted to the 39th Battalion. In October of that year, he deployed overseas to France with the 42nd Battalion. Ernest remained in France with the 42nd for two years, only taking leave in April and November of 1917.

In February 1918, Ernest Auld was promoted to temporary Lieutenant upon posting to the 3rd Divisional Signal Company. Only 3 days after, Lieutenant Auld was posted to the 3rd Div Wing Canadian Corps Reinforcement Camp (CCRC). In July, he took a 14-day leave of absence. Less than two weeks after his return from leave, Lieutenant Ernest Auld was reported Killed in Action on 7 August 1918. He was 21 years old.

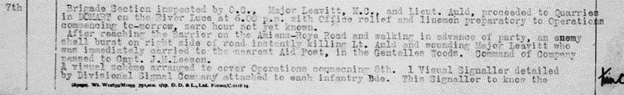

The entry in the War Diary of the 3rd Canadian Divisional Signal Company for the day of his death reads:

“Brigade Section inspected by O.C., Major Leavitt, M.C., and Lieut. Auld, proceeded to Quarries in DOMART on the River Luce at 6.00 p.m. with Office relief and linemen preparatory to Operations commencing to-morrow, zero hour not yet known.

“After reaching the Barrier on the Amiens-Roye Road and walking in advance of party, an enemy shell burst on right side of road instantly killing Lt. Auld and wounding Major Leavitt who was immediately carried to the nearest Aid Post, in the Gentelles Woods. Command of Company passed to Capt. J.H. Leeson.”

Lieutenant Ernest William Auld was buried in Longeau British Cemetery in Longeau, France. His headstone, commissioned by his mother, Margaret A. Pomeroy, reads:

“PRO PATRIA NON TIMIDUS MORI”

Which translated (via Google Translate) reads:

“NOT AFRAID TO DIE FOR COUNTRY”

-Article by Capt Sean Maas-Stevens

Excerpt from the enlistment documentation for Lt Auld

Excerpt from the War Diary of the 3rd Canadian Divisional Signal Company for 7 August 1918