Welcome to the June 2024 edition of The Despatch, the Military Communications and Electronics Museum Newsletter.

80 Years Ago-The Normandy D-Day Invasion

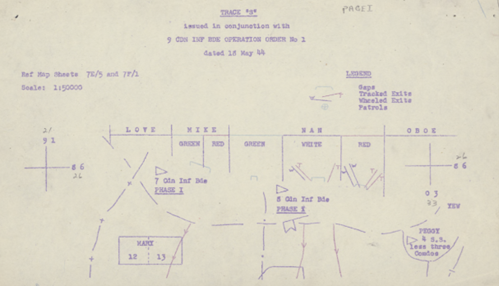

More than Another Scheme: Operation OVERLORD as observed by the Highland Light Infantry of Canada

Foreword and Compilation: Sean Maas-Stevens

References:

A. War Diary of the HLI - http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=927780&lang=eng

B. List of Canadian Army Units in the Normandy Landings - https://www.junobeach.org/canada-in-wwii/articles/d-day/canadian-army-units-in-the-normandy-landings/

C. Image of HLI going aboard LCI(L) 276 - http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=3191499&lang=eng

D. Image of the Normandy Landing taken from LCI(L) 306 - http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=3208962&lang=eng

E. Historical Canadian Military Abbreviations (referenced throughout) - https://wartimes.ca/research/abbreviations/

Foreword:

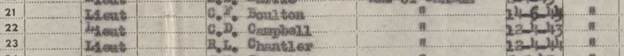

In the war diaries I have read in my research of the First World War, the information held was often sterile, clinical, and to the point. A statement on the weather, a note on troop disposition, and the names and nature of any casualties experienced over a 24-hour period. While researching for an article about the Beach Landing at Normandy in 1944, I came across a war diary unlike the others. Here I hope to present the timeline of events experienced by the soldiers of the Highland Light Infantry of Canada in photographs and words of their war diary. While I have not been able to definitively determine the author, they have initialed next to their entries as C.D.C. The best I can tell, this could be Lt C.D. Campbell, an officer in the HLI noted in the file at ref A. In particular, this piece will focus on the lead up and execution of the D-Day landing from the HLI perspective.

Name of the possible author in the HLI Officer Nominal Roll from 24 June 1944 (Ref A page 70)

2 June 1944

“…Everyone is writing letters, sun bathing and reading. HLI officers in the camp between [Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry Highlanders (SD&G)] in a ball game. – 16-15… At the beginning of the 9th inning the score was 16-3 for HLI but then they blew [it]. Dick Stauffer brought the game to an end when he made a leap for a hot drive and caught it.”

3 June 1944

“Hottest day in the past decade. Temperature 100° in the Straits… HLI again beat SD&G officers in a ball game. Move ordered for 2230 hrs but postpones until 0400 hrs. Sea stores, bags ration, tommy cookers, bags vomit, sea sick pills, etc, were drawn from stores and blankets turned in and later redrawn.”

4 June 1944

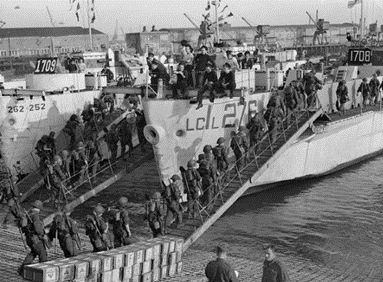

“Serials were awakened at 0200 hrs to turn in blankets and have break-fast. At 0300 hrs the first serial left in [Troop Carrying Vehicles (TCVs)] for the embarkation pt. Tea was served on the hards to all serials before embarking. There was a little delay while bicycles, blankets, rations, etc, were loaded, but all tps embarked without mishap and were soon asleep. All crafts but the one drawn by B Coy were equipped with cots in tiers… As all were on the floor it was much more crowded than other crafts. It was almost necessary to sleep in shifts.”

HLI Troops Going aboard LCI – Credit: Gilbert Alexander Milne / Canada. DND / Library and Archives Canada / PA-132811 (Ref C)

“At noon hour the tps left the tp decks and began to wash up before dinner. An addition of self heating cocoa and white bread… met with the approval of all.

“Sailing was cancelled due to rough water in the channel. At 1600 hrs all ranks were marched (under a security guard) to a recreation centre set up in several adjoining railway sheds. Here every man got a good wash and clean up in hot water, followed by an excellent meal. White bread, coffee and peaches – and lots of it, were the highlights of the meal… [A]ll men who wished were allowed an advance in pay in order to make last minute purchases. Every man was given 25 cigarettes – the gift of the Canadian government. Tribute should be paid to the splendid organization of the transit camps through which we passed. Food and accommodations were of good quality. Many extras were provided. It made us feel that some of our trips through the “sausage machine” pushed hither and yon by movement control had served some purpose… Morale is high, though everyone is disappointed at the post ponement and many refuse to believe that this is anything more than “another scheme” in spite of more extreme preparations.”

5 June 1944

“The first definite indication we received that the operation was to be on, was the issue of sea-sick tablets about 10 O’clock in the morning. While the news of the invasion met with high approval the idea of the need for the pills was far from comforting. However the sky still looked angry and there was a threat of wind in the air.

“At approximately 1330 hrs the craft began to slip out of the harbour. There were no bands or cheering crowds to give us a send off on the biggest military operation in history. A few dock workers silently waved good-bye. Friends called farewell and bon voyage from one craft to another. A few craft blew their whistles and up on the bridge Sagan the piper played “The Road to the Isles[.]” The 9th “Highland” brigade was on its way.

“As we passed out of the harbour and toward the boom we were met by many more streams of like craft. Once past the boom the great armada began jockeying for position and the wind puffing up its cheeks blew until he tossed the tiny craft about like straw – necessitating a second issue of pills.

“By this time, many began to disappear from the deck to the tp decks below, there to hide their miserable efforts at composure. Some sat upon the deck and watched the huge fleet that had assembled. There were craft of every type imaginable. There were blunt nosed [Landing Craft-Tank (LCTs)] butting their way along, small [Landing Craft-Infantry (LCIs)] riding the crests like corks, big channel packets with their [Landing Craft-Assault (LCAs)] lashed to their sides and proud cruisers running hither and yon in search of an enemy who would dare to poke his head out of the water. In the distance big “battle wagons” lent an air of confidence and security to the scene.

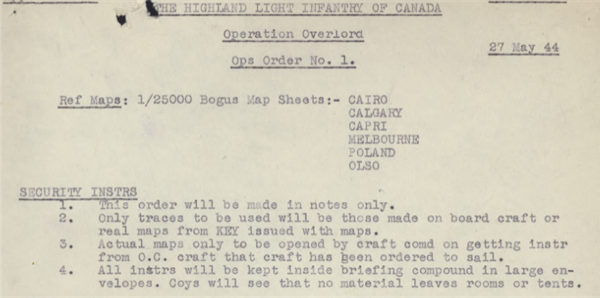

“At 1600 hrs, when well past the shores of England, sealed bundles of maps were opened and distributed. For once there were no complaints of a scarcity of maps as the issue was down to section leaders. Officers received various other maps to aid in the briefing and subsequent planning.

“It was only when maps were opened that tps were told where they were going, that exercise Overlord was indeed the real thing and not just another exercise. It was only then that they learned that “Poland” on the bogus maps was really Caen.

“The remainder of the day was spent briefing the tps. The plan that they had gone over so many times before was again reviewed and the real names of places were given… Messages from General Eisenhower and General Montgomery were read to the tps.

“Fortunately, the briefing had been well done previous to landing as many were too sea sick to evoke much interest. As night bore down the sea got worse. Many spent the night on the deck in a driving rain – just to save time. Others lay below in a miserable heap and evoked the gods that be to do their worst as nothing could be any worse. Few were interested in eating that night – a sure proof of their misery. Those leaning over the rail lost complete faith in the effectiveness of sea sick pills – and that[’]s not all they lost.

“So the day ended and the HLI of C many thousands of miles away from the Galt where they had started from many of them nearly four years previously were on their way to France to “fight our countries battles, til the day of victory”.”

6 June 1944

“Daylight broke on D day and presented rather a dismal picture from the weather standpoint… The sky was dull and threatening… The decks were lined with tps long before daybreak. Some had got up around 0400 hrs to watch the flashes given out by the guns as the 6th Airborne Division and Commandos on our left flank attacked the strong coast batteries and vial bridges. Some were huddled in blankets in the throes of sea-sickness and not the least bit interested in the war. For them the war would only begin when they set foot on good old “tera firma”. Others preferred sleep and an anti dote to the “ol misery” in the stomach. With the light came an impressive sight. The sea as far as eye could reach was dotted with craft. Little LCIs bobbing along on the high waves, blunt nosed LCTs smashed clumsily into the swell, trim destroyers racing up and down among the fleet in search of underwater enemies and great battleships riding proudly in the distance. One felt awed by the immensity of the picture and at the same time comforted by the presence of such a large number of “big ships” ready to lend the support of their powerful guns.

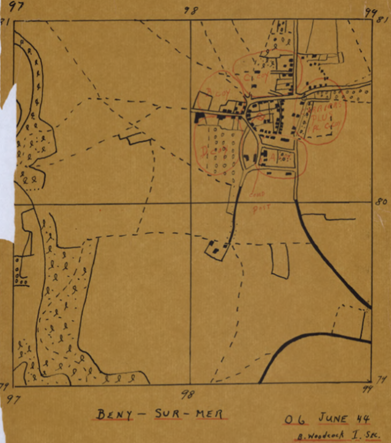

Initial Landing Plan for Phase 1 on D-Day (Ref A page 208)

“About 0700 hrs we came in sight of the shores of France. Our tps were just getting up as they still had plenty of time before their run in. Soon we could make out the little towns along the coast and were

able to get our bearings. Firing could be seen coming from some of the buildings and the presence of LCAs going through us to our rear told us that the assaulting brigades had gone in.

“Then came the exasperating part of the invasion for us. About 0900 hrs we were told to prepare to land. Everyone got into their eqpt and then spent the next two hours “stooging” around the channel in big circles waiting for the “run in”. The 7th bde on our right flank appeared to get in with little trouble. The 8th bde front seemed to be a little slower especially on the left around St.Aubin where the North Shore Regt seemed to be meeting stiff opposition. Fires broke out in some of the houses on the rt flank of the 8th bde.

“Shortly after 11 o’clock we were informed that the HLI would not land on Red Beach in the vicinity of St.Aubin as the opposition had been so strong that the assault tps had not succeeded in getting far inland. We later learned that the Radar station near Tailleville was much more heavily defended than we had expected.

“At approximately 1140 we made our “run in” to White Beach in front of Bernieres-sur-Mer. All the LCIs bearing the rifle coys touched down almost to-gether. The Navy did an excellent job getting us ashore as it was one of the driest landings we had managed in some time, being only knee deep. As soon as the ramps were lowered men began to stream off carrying bicycles. The only mishap was in the beach-ing of [the] B Coy boat which carried the C.O. and his command gp… No one was injured.”

HLI LCI on the beaches at Bernieres-sur-Mer - Credit: LS Wallace McQuade / Canada. DND / Library and Archives Canada / PA-137016 (Ref D)

“The beach itself was in a terrible [confusion]… the beaches were jammed with tps with bicycles, vehicles and tanks all trying to move towards the exits. Movement was frequently brought to a standstill when a vehicle up ahead became stuck. It was an awful shambles and not at all like the organized rehearsals we had had… One gun ranged on the beach would have done untold damage…

“We had not gone many yds inland when we met the rear elements of the 8th Cdn Inf Bde. The streets of the shattered village were blocked with rubble from the heavy preparatory shelling and bombing. In the neighbourhood of the church we were held up. We could go no further as the roads were blocked by the transport of the assaulting bns. Well placed [machine gun (MG)] posts and snipers had caused the [Queen’s Own Rifles (QOR)] to deploy and attack them…

“It was in Beny-sur-Mer that our unit had its first real contact with the enemy. We were continuously mortared as we stopped in the village. There were no casualties, but some dropped uncomfortably close.

“While awaiting the order to move tps could be seen with a book in one hand read-ing off French phrases much to the amusement of the inhabitants. Beny-sur-Mer had had a German barracks and the Germans were hardly out of the village before the inhabitants began to loot the place. Men struggled with bags of flour, a wheelbarrow full of army boots, a hind leg of beef, chairs, clothes, boxes of black rye bread, butcher’s saws and countless other articles. Women came by with chickens, butter, curtains, sheets, pillows, dishes, cutlery, bowls, etc. Even the parish priest was seen to carry off a set of dishes. People were all excited and friendly, offering us their best luck, glasses of milk and wine.

“Just as we were ready to move on, at approximately 2145 hrs, the order came to stay where we were for the night. The NNS were to stop at Villons-les-Buisson with the SD&Gs on their right and the HLI in the rear… It was fast getting dark and we hurriedly dug in our defensive positions around the village. Reports of enemy armour moving north out of Caen put us on our mettle and we prepared to receive a possible armour counter-attack earlier than we had anticipated.

Planned positions for the HLI at "Beny-sur-Mer" on D Day (Ref A page 84)

“Thus ended D Day our first day in Normandy. Little sleep was had that night but no one cared. Although not a shot had been fired by our bn as yet, we were on enemy soil, and at the end of our four years of waiting. Some were a little disappointed that we had not yet tangled with the enemy and felt a personal reproach that we had not succeeded in reaching the airport[,] our objective. But war always travels more slowly than schemes as the unexpected enters in. The 8th bde on our front had reached their objective although their left flank was trailing. The 7th on our right had reached their objective with little trouble. We were in a position to push through the 8th in the morning and attack our objective[,] so tomorrow would be another day.”

80 Years Ago-The Invasion of Italy

On June 4th, 1944 the Allied armies entered Rome and the 1st Canadian Corps went into reserve. As the Allies entered Rome, the Germans were falling back to their next strong defense system, the Gothic Line. The Gothic Line stretched across the peninsula from Pisa to Pesaro. Even though the 1st Canadian Corps was in reserve, signals units continued to work. Attached to the Engineers, the Core Engineer Signal Section diligently supported the communication needs as roads and bridges were built and mines cleared away. Administrative missives were sent back and forth as the Corps prepared for the next battle. The 1st Armoured Signal Brigade never actually stood down over the summer as all of the tanks were deployed to other formations.

Entry of Allied forces into Rome, Italy, 4 June 1944. Credit: LAC

Karen Young, Museum Volunteer

Coffee with Veterans

Museum Summer Hours

Museum Summer hours begins July 2 to Labour Day, September2, 2024. The Museum will be open 7 days a week, 1000-1530.

Not Forgotten – Paul Angus MacGillivray – 541626

References: A. http://www.rcsigs.ca/index.php/Signals_Casualties_of_the_Great_War_-_Details#MacGillivray_Paul_Angus

B. https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item/?op=pdf&app=CEF&id=B6842-S011

C. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/remembrance/medals-decorations/details/49

D. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/en/remembrance/medals-decorations/details/53

E. http://www.rcsigs.ca/index.php/File:MacGillivray,_Paul_Angus_medal_card_MM.jpg

F. https://www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/59982/p-a-macgillivray/

Paul Angus MacGillivray was born on 14 July 1895 in Moncton, New Brunswick. Leaving his work as an electrician, he enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) on 11 June 1915 in Halifax, Nova Scotia and was appointed the rank of Sapper.

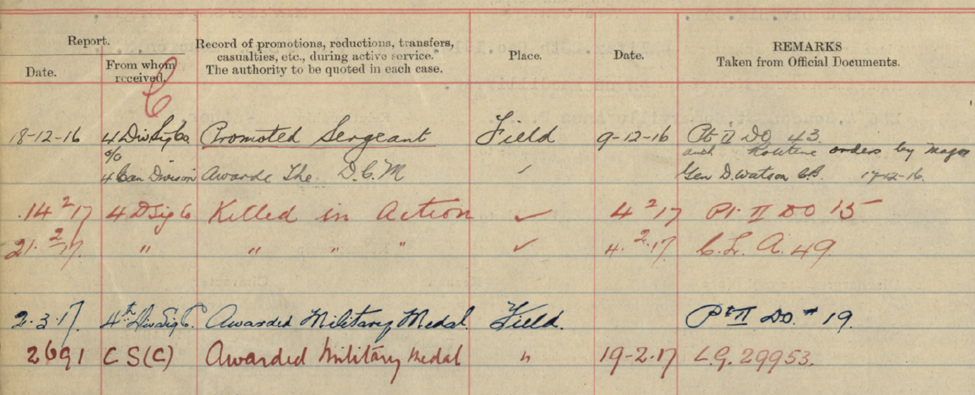

Arriving in England in April of 1916, having already been promoted to the rank of Sergeant, Paul was reverted to acting Sergeant upon being taken on strength in Shorncliffe, UK. Less than a month later, A/Sgt MacGillivray was transferred to the 4th Divisional Signal Company in Bramshotte. A/Sgt MacGillivray was reverted in rank to Acting Corporal in July of 1916, before being deployed in August to the field.

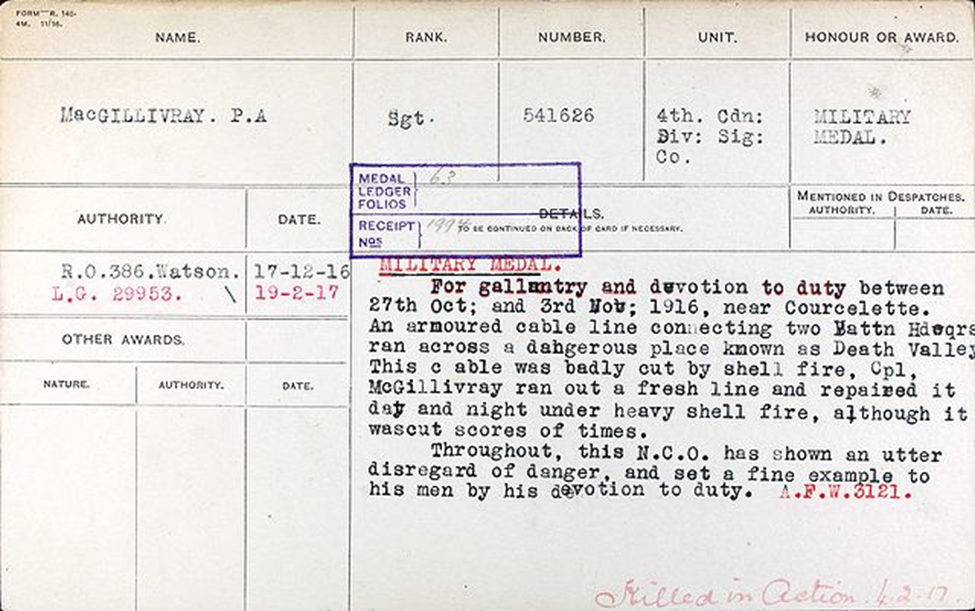

While in the field, following a promotion to substantive Corporal, Cpl MacGillivray was nominated for the Military Medal “For gallantry and devotion to duty between 27th Oct; and 3 Nov; 1916…” (Ref E) During that period, he repeatedly repaired an armoured cable line in an area known as Death Valley, near Courcelette. While the nomination likely came shortly after the events which led to the award, it was not approved until 19 February 1917.

In December of 1916, Paul was promoted to Sgt, and on that same day Sgt MacGillivray was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM). According to Veterans.gc.ca (Ref C), the DCM was awarded for “distinguished conduct in the field. It was the second highest award for gallantry in action (after the Victoria Cross) for all army ranks below commissioned officers…” His award was authorized by MGen D. Watson on 17 December 1916.

Sgt Paul Angus MacGillivray was killed in action on 4 February 1917. He is buried in Villers Station Cemetery, in Villers-au-Bois. His headstone reads (Ref F):

541626 SERJEANT

P.A. MACGILLIVRAY MM

4TH CAN. DIV. SIGNAL COY

4TH FEBRUARY 1917

Capt. Sean Maas Stevens

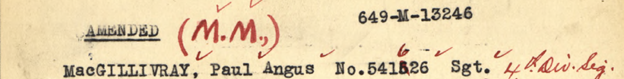

Medal Authorization for the Military Medal for Sgt MacGillivray (Ref E)

Excerpt from Sgt MacGillivray’s Personnel File showing the awards of the DCM, MM, and promotion to Sergeant (Ref B)